Why ‘Zero Trust’ Cybersecurity Fell Short of Revolutionizing the IT Field

Discover the shocking truth behind why ‘Zero Trust’ cybersecurity failed to transform the IT landscape, and what it means for the future of digital security.

Over the past decade, extensive discourse has surrounded the foundational concept in cybersecurity known as zero trust — the core principle that no user or device on a computer network can inherently be trusted. However, despite the considerable attention it has received, widespread implementation has not been achieved to the extent one might anticipate.

The challenges encompass a multitude of practical and perceptual hurdles, along with a complex collection of products that need careful coordination to deliver on its promises. As such, zero trust won’t serve as a silver bullet for the ongoing cybersecurity obstacles anytime soon.

The concept of zero trust originated with John Kindervag during his tenure as an analyst at Forrester Research in 2010. The premise behind zero trust is that companies must verify every file request, database query, or network action to ensure they originate from users with appropriate privileges. Any new devices must undergo registration and validation before accessing network applications, and each user login attempt is treated with suspicion until proven otherwise. When implemented effectively, zero trust holds the promise of liberating users from the constraints of conventional cybersecurity methods, thereby enhancing defense mechanisms.

After conceiving the idea, Kindervag proceeded to establish a management services provider offering one of the numerous solutions attributed to his creation. Nearly all leading security providers feature a service or product incorporating the term as a part of their service offerings, with notable announcements from industry giants like Cisco Systems Inc. solidifying their stake in the zero-trust domain.

In practice, despite the abundance of available products, a comprehensive zero-trust solution still proves largely incomplete, often resulting in unused implementations. John Watts, a Gartner analyst, highlighted in last December’s annual predictions memo that “transitioning from theory to practice with zero trust is challenging.” He noted that fewer than 1% of large enterprises are currently utilizing it.

Watts also predicted that “over 60% of organizations will embrace zero trust as a starting place for security by 2025, but more than half will fail to realize the benefits.” A report from Nathan Parde of MIT’s Lincoln Lab estimated that the typical zero-trust deployment will take three to five years. Such a timeline is undoubtedly a depressing thought.

These findings contrast with surveys conducted by other providers, which paint a more optimistic picture. For instance, Okta Inc.’s State of Zero Trust Security August 2022 report revealed that nearly all of the 700 surveyed organizations have either already initiated a zero-trust initiative or have concrete plans to do so soon.

Yet, these findings may be somewhat misleading. Firstly, significant time lapses could occur between the initiation and completion of a zero-trust rollout. Secondly, a disconnect often exists between verbal intentions and actual organizational actions, with surveys potentially biased toward selecting respondents favoring zero-trust implementations.

Quick Overview of Cybersecurity

The evolution of network infrastructure segregation for enhanced resource protection can be traced back to the emergence of the first network firewalls and virtual private networks (VPNs) in the mid-1990s. DarkReading explored this topic in 2008, examining the origins of the firewall, commonly attributed to Check Point Software Technologies Ltd., a company still active in its development and distribution. Regarding the first VPN protocols, it is widely agreed that they were created by Microsoft Corp. in 1996, gaining popularity around the turn of the century and continuing to be offered by industry leaders such as Cisco, Juniper Networks Inc., and others.

What firewalls and VPNs accomplished was to separate networks by enacting various policies. For instance, they permitted network traffic from internal marketing databases in certain areas while restricting traffic from internal personnel databases. Or queries from external networks were permitted to access a corporate web server, but not any other part of the network. The formulation of these policies constituted the proprietary techniques of these products, requiring cybersecurity specialists to undergo extensive training to understand.

While effective during the era of rigid and well-defined network perimeters, the advent of scattered web applications across the online landscape rendered it no longer a viable concept, and impossible to enforce. As businesses increasingly relied on intricate software supply chains, their dependency on application programming interfaces grew, resulting in less insight into how the various software pieces fit together.

Such circumstances are how many exploits arise as malicious actors capitalize on the inherent vulnerabilities, knowing they can eventually breach a network. VPNs and firewalls became new security voids, especially as more untrusted remote devices joined corporate networks.

Enter Zero Trust

This is where Kindervag’s zero-trust philosophy emerged. According to him, trusting anyone or any application without verification is not viable. This approach, often referred to as “least privilege” by security professionals, ushered in an era of adaptive authentication. In this model, individuals and applications are not granted full access from the outset. Instead, organizations gradually approve access based on specific circumstances.

For example, if you query your bank for a current balance, you must provide proof of account ownership. But if you want to transfer funds, additional verification is required, and if you intend to transfer funds to a new overseas account, even more stringent authentication measures are necessary.

Modern zero trust principles have introduced the notion of a “trust broker” — a mediator or neutral third party trusted by both sides of a transaction. Setting these up, particularly among both parties lacking direct knowledge or trust in one another, poses challenges, especially if different brokers are required for different situations, apps, and types of users.

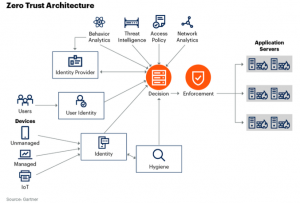

That complexity alone is where we stand with today’s zero-trust implementations. NetIQ, now part of OpenText Corp., said in its “State of Zero Trust In The Enterprise” report, “Having enterprise systems, applications, and data in one location and relying on layers of security tools and controls to keep attackers out is no longer sufficient when the bulk of data and workloads now live outside the traditional network. Zero trust is not a single piece of software but a strategic framework.” One way to grasp this concept is through Gartner’s architectural diagram, which illustrates it as a series of interconnected parts, including user identity management, threat intelligence, and application security.

Now, let’s take a closer look at both the “strategic” and “framework” aspects and what they mean for zero-trust implementations. Strategic means that at the core of any solid cybersecurity plan, “there must be a strong emphasis on zero trust.” This aligns with the objective outlined in President Biden’s Executive Order on Improving the Nation’s Cybersecurity from three years ago, which aimed to inspire federal agencies to adopt zero-trust security measures.

While commendable, the realization of this objective remains distant. Even an executive order cannot immediately enforce the adoption of zero-trust measures. Although made recently, federal agencies were instructed to restrict internet access to various networked devices, including VPNs and routers, something that should have been obvious by now to any information technology manager.

While commendable, the realization of this objective remains distant. Even an executive order cannot immediately enforce the adoption of zero-trust measures. Recently, federal agencies were told to restrict internet access to various networked devices, including VPNs and routers, a measure that should have been obvious to any information technology manager by now.

Rethinking Trust

Perhaps, many individuals have been approaching zero trust from the wrong perspective. Trusting a user or an application exists on a spectrum, like adaptive authentication: it begins with gradual steps towards complete trust, providing small increments over time. Shifting away from the binary all-or-nothing mentality, this “incremental trust” model aligns better with the complexities of today’s environment.

One way to conceptualize this is to consider adopting micro-segmentation to isolate applications, essentially refining firewalls to target specific workloads and users. According to Gartner’s Watts, this involves “implementing zero trust to enhance risk mitigation for the most critical assets initially, as this is where the greatest return on risk mitigation will occur.”

Gartner uses five considerations to define zero trust: identifying what the delivery platform is, how to enable remote work securely, how to manage the various trust policies, how to protect data anywhere and what integrations with third-party products are there. These aspects represent numerous touchpoints, essential for either a framework or a series of products to effectively deliver on zero trust principles.

Zero trust can manifest as a mindset, paradigm, or strategy, and in the implementation of specific architectures and technologies,” stated Watts in his predictions report. He offers several recommendations to enhance organizations’ success in its implementation, including defining the appropriate scope and level of sophistication of zero-trust controls at the beginning of a project, limiting access to devices and applications, and applying continuous risk-based access policies.

Fundamentally, zero trust means removing the implicit trust (and the proxies for trust) that have formed the foundation of many security programs, with explicit trusts based on identity and context,” he said, “This will require changing the way security programs and control objectives are defined and especially changing the expectations about the level of access.

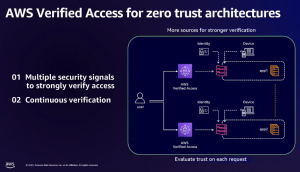

Amazon Web Services Inc. at its recent re: Inforce conference in Anaheim, California, showcased examples of how this approach will function. Jess Szmajda, the general manager for AWS’ Network Firewall, demonstrated the integration of existing zero-trust services like Verified Permissions and VPC Lattice with a range of new offerings to bolster AWS’s security posture. These new services include Verified Permissions and enhanced features for its GuardDuty threat monitoring tool, providing improved granularity of security policies and additional preventative controls. Amazon refers to this as “ubiquitous authentication.”

In essence, organizations should anticipate a lengthy and intricate journey toward implementing zero trust. But, if they can demonstrate the immediate business benefits, it’s worth taking those first steps.